- Home

- David Hughes

Tales From Development Hell Page 2

Tales From Development Hell Read online

Page 2

The second act sees Robert-Houdin, Colette and Darcy set off for the desert palace of Bou-Allem, the most influential Arab sheik in the country. “Bou-Allem, a devout seeker of truth, is still flirting with the rebels, waiting to be convinced as to whose side to take — Berber or French,” the Batchlers explain. “So he summons Robert-Houdin to a one-on-one command performance — basically a showdown against the rebellion’s chief sorcerer.” Though the odds are stacked against him, Robert-Houdin beats the sorcerer Zoras at his own game, totally disgracing him even in the eyes of his own men — and reminding the magician of his former glory. “We then weave elements from other historical research to create the climax for our story,” the Batchlers add, “which involves the trek from the desert wilderness back to Algiers via the treacherous Kabyle Mountains, where Robert-Houdin and his party are ambushed by a loyal remnant of the disgraced sorcerer’s army.

Our heroes take refuge and fight it out inside an ancient abandoned tenth century citadel, which we patterned after real fortresses that once existed in those mountains. Outgunned and outmanned, Robert-Houdin must marshal all his magician’s cunning in order to defeat his foes inside that fortress.” Thus, the stage is set for an exciting third act in which Zoras seeks vengeance for his humiliation at Robert-Houdin’s hands.

On 5 January 1993, after nine drafts, the Batchlers were finally ready to type ‘FIRST DRAFT’ on the title page of the script. “We weren’t sure what to do,” Janet later recalled. “We had no access to anyone who would be able to make a picture this big.” After sitting on the script for more than a month, Janet called an acquaintance at Longbow Productions, a small production company which had one big film to its name: the women’s’ baseball picture A League of Their Own. Although Longbow partner Bill Pace felt the script needed work,

he liked it enough to take an option on it, paying a token fee (typically one dollar) to the Batchlers, before sending the script to Howard Koch, Jr., who had a production deal at Paramount Pictures. Koch liked it enough to send it to the William Morris Agency’s Alan Gasmer. “Alan did a great job of talking it up without letting anyone see it,” says Janet, “and more and more people began to ask for it.”

Around town, as well as at the Sundance Film Festival, Gasmer let it be known that this project was about to come up for auction. He had sent the script out to various studios and producers, as is customary, hoping for a call-back from at least one of the few with the power and resources to option or purchase outright a script whose historical setting, special effects, star-driven subject matter and epic scale demanded a budget estimated at $55 million: Universal Pictures, Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, Columbia-controlled TriStar, Warner Bros and The Walt Disney Company. “It was a movie-movie, like Romancing the Stone, Star Wars or Indiana Jones, with a Lawrence of Arabia scope to it because it had the desert and castles and such, and it came down to what studios had the nerve and the big bucks to pony up and say, ‘We want to play this game.’”

Among those to whom Gasmer had pitched the project was Jay Stern, a development executive at Disney-owned Hollywood Pictures, over lunch at The Grill in Beverly Hills. Stern’s response was immediate, and enthusiastic. “Sounds great,” he told Gasmer. “Please, I want this. That’s one I would really, really like to get my hands on.” Stern got his hands on the script the following Tuesday, and took it home with him, planning to read the first forty pages (typically, the first act of a 128-page script) before bed. Instead, he finished it. Stern called Gasmer first thing the following morning, and left messages with Interscope and Cinergi, two production companies with which Disney might share the costs of the mega-budget project.

Arriving at his company’s regular Wednesday morning story meeting, Stern pitched the story to his superiors, including Hollywood Pictures president Ricardo Mestres and Disney chief Jeffrey Katzenberg, telling them that it was big, original, well executed, distinctive — and definitely going to be snapped up fast by a rival studio if they did not make a move on it. Mestres read the script that morning and agreed that Disney should bid, and immediately sent the script to Andrew G. Vajna, the Hungarian-born founder of Cinergi and producer of such big-budget films as Judge Dredd and Super Mario Bros. Unfortunately, at nearby Warner Bros, executive Tom Lassally had made the same assessment, and called Gasmer to ask what kind of deal his clients were looking for. “I’m looking for a million,” Gasmer told both interested parties,

with typical agent chutzpah. By Friday, after newly-installed Paramount production head Tom Levine had passed on the project, Gasmer had Disney, Warner Bros and TriStar readying their cheque books.

TriStar had already sent the script to Wolfgang Petersen, the German-born director who would later direct In the Line of Fire and The Perfect Storm. “I don’t know if they got an answer from Wolfgang,” Stern told Thom Taylor, author of The Big Deal: Hollywood’s Million-Dollar Spec Script Market, “but it was Friday afternoon and I knew that [Warner Bros executive] Bruce Berman was unreachable.” Indeed, Berman was snowed in at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, stuck on the tarmac on on United Airlines Flight 7 to Los Angeles, and therefore unable either to leave the plane, or even use his cellphone.

This being Hollywood, Stern used Berman’s predicament to his advantage: “I was concerned that as soon as Lassally reached Berman and had the conversation, that they would just put a million dollars on the table.” With Disney’s Mestres and Cinergi’s Vajna agreeing to split the development costs, with Katzenberg insisting that Disney’s exposure be limited to $14 million, Stern made Gasmer an offer he knew his clients could not refuse: one million dollars, with an additional commitment to commission the Batchlers to write another script, to be decided upon at a later date. Gasmer, however, was unable to reach his clients, who were en route to a weekend-long writers’ group seminar in Cambria, some 220 miles north of Los Angeles.

“Friday, the day the auction was coming to a close, was the day we were scheduled to drive up the coast to meet everyone for the weekend,” the Batchlers recall. “Because this was back in 1993, we didn’t have a cell phone, and had to stop every fifteen minutes or so, pull off the road, and find a pay phone to check in with Alan to see how things were going. We know his inability to get hold of us was somewhat frustrating to the people bidding — at one point an exec told him, ‘Get your clients to a phone and get them to stay there!’ — so eventually, we stopped at a small courtyard motel outside Arroyo Grande and stayed on the phone for about an hour, responding to the final bidding, until the deal was done.”

Giddy with excitement, the Batchlers celebrated in style, treating the other members of their writers’ group to dinner. “Unfortunately, that particular weekend we may have had the sale but didn’t have the cash in hand, so we had to borrow money from one of the other writers to actually hold the celebration dinner. We were rich on paper, but cash-poor.” The facts remained, however: the Batchlers had a seven-figure commitment from a major studio. Their names were now known by some of the most powerful

people in Hollywood. And their script was on the fast-track at Disney.

While the feeding frenzy surrounding Smoke and Mirrors was not uncommon, what happened next was unusual to say the least: within three weeks, the script had achieved ‘go movie’ status. Immediately after the option deal was signed, Ricardo Mestres had secured the services of producer, director (and amateur magician) Frank Marshall, who had helmed the Disney hits Arachnophobia and Alive, and produced several Steven Spielberg films. Although Marshall had recently signed a deal with Paramount Pictures, he retained the freedom to direct a picture elsewhere, and Smoke and Mirrors was immediately elevated to the top of his own personal script pile.

Meanwhile, Vajna managed to interest Sean Connery (who had just starred in Cinergi’s Medicine Man) in the lead role of Robert-Houdin, a development certain to attract other A-list stars to the film’s other principal roles: Colette, Robert-Houdin’s glamorous wife, and Darcy, the dashing American who accompanies the

pair on their trip into the desert. But as the Batchlers were preparing to bathe in the glow of the film’s green light, the title Smoke and Mirrors proved to be prophetic. “We thought it was a wonderful script which just needed some work on the ending,” Vajna told Neil Rosser, producer of a BBC radio documentary adapted from the first edition of this book. “We enlisted Kathy Kennedy and Frank Marshall to produce and Marshall to direct; we had Sean Connery signed up as the star of the movie and we were looking at locations, but we were still working on the script, and somehow we could never get the end of the story right.”

Firstly, Sean Connery allegedly slowed the pre-production process by requesting rewrites, as is customary with A-list actors, to tailor the script to his own style. Lee and Janet Scott Batchler churned out several subsequent drafts, the last being a 132-page fourth draft dated January 1994. “We were very involved with the development of the project during its Sean Connery phase,” say the Batchlers. “Sean was attached within days of the script being sold, as were Frank Marshall and [producer] Kathy Kennedy. We met with Sean to get his notes, and spent months working with Frank and Kathy. [They] were great to work with in every respect and we think the world of them. We did three rewrites while working with Frank Marshall and Kathy Kennedy on the project. We were really focused at that point on getting the script ready for production,” they add. “We were very happy with the fourth draft of the script, which was the culmination of our rewrites. The original script is powerful for reasons of its clean, uncomplicated approach to the storytelling — it’s just a great ride, start to finish. [But] we personally feel the fourth draft deepened the main characters and added several plot elements that actually improved on the original while retaining what was important.”

Sean Connery did not share their enthusiasm, however; although he remained attached to the project, he insisted upon further rewrites, by which time the Batchlers had been hired by Warner Bros’ Bruce Berman to write Batman Forever, the third installment of the studio’s most profitable franchise. In their place, the Smoke and Mirrors producers hired Alive and Congo screenwriter John Patrick Shanley to rework the story; the inevitable result being that Connery’s rewritten role diminished the supporting roles, Darcy and Colette, making them more difficult to cast. By the time Shanley turned in his draft, Frank Marshall had departed to direct Congo for Paramount, leaving Smoke and Mirrors without a director. Connery and Shanley parted company with the project soon afterwards, at which point John Fasano (Another 48 Hrs.) and Douglas Ray Stewart (An Officer and a Gentleman) took turns at the script. Since screen credit and remuneration tends to be apportioned depending on each screenwriter’s contribution, however, both Fasano and Stewart may have been inclined to change elements which might otherwise have fallen under the caveat of ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ Thus, the script began to move further and further away from the one which had excited Disney in the first place, and closer to ‘Development Hell’.

Then, in late 1994, Cinergi development executive Brett Fain brought in a young writer named Ted Henning, whose script for an unproduced pirate adventure, Caribbean Blue, suggested that he might be suitable to mount a salvage operation. “He was a very smart guy and very [committed] to creating a version of the script that the company could actually make,” Henning observes of Fain. “Each had some interesting aspects, but none was shootable — none would make a great movie,” Henning says of the previous drafts, all of which Fain showed to him. “They all lacked a sense of fun that we felt was imperative for the movie to connect. [The producers] wanted Indiana Jones meets Lawrence of Arabia. Most of the scripts were the latter with none of the former — though one was so confusing I couldn’t figure out which line it fell on.” Henning dismissed Stewart’s draft as “unreadable”, but liked Fasano’s take on the material. “It was really detailed,” he says. “He’d done all this research; you could tell. He brought in the hashashim, a really violent cult in Algeria in Northern Africa, which gave us the word ‘assassin’.”2 “He brought some incredible detail to it,” adds Henning, “but I think he got bogged down in the detail. I went back to the Batchler draft and started from there, working very closely with Brett to create a tight, fun epic that would stay as true to the story as possible while connecting with the largest audience possible, to warrant the $100 million-plus the movie would cost to make.”

The nature of their producer-writer collaboration was unusual: instead of taking Fain’s notes and delivering a script a few months later, Henning would write ten or fifteen pages at a time, and then go over them with Fain to see if the script was going in the right direction. “It was a really close [working relationship] which a lot of screenwriters wouldn’t like,” he says. “But Brett was a really smart guy. He had been through all the permutations, and had a really good sense of it.” Both knew that the script’s biggest flaw was structure. “The movie is about Houdin going to Algeria, and then what happens over there, so you have to set him up in France, put him in some situation where he’s vulnerable, and then get him on the boat. [The Batchlers] didn’t get him on the boat until page fifty.”3 Although Henning and Fain liked the Batchlers’ script, both felt that it lacked focus, that Robert-Houdin’s character arc was weak, and that it failed to realise the potential of the Robert-Houdin/Darcy/ Colette love triangle.

“Structurally, we got it down,” Henning says. “We also made really strong decisions about Houdin’s arc,” he adds, noting that, in all subsequent drafts, Robert-Houdin’s name was further simplified to ‘Houdin’ — presumably for the convenience of the same audience who could not be trusted to pronounce ‘Jean-Eugène’. “We started him off as this powerful magician who was on top of the world, and we just flushed him down the toilet. He was disillusioned; he had killed someone with a magic trick [when] something had gone terribly wrong. In real life, it actually happened — I think his son or daughter was killed — and he basically then switched over to science and became a big debunker, and tried to find the reality of his world, because up to then he’d been living the illusion of celebrity. So when we found him [in the story], he hadn’t been out of the lab in six months, and his girlfriend [rather than wife] Colette was at the end of her rope, so when he is asked to go to French-occupied Algeria, she says, ‘If you don’t go, I’m leaving you.’ He figures he’s going to debunk this guy as a fake, and then leave. Of course, as soon as he gets there, things start happening to draw him deeper and deeper

into it, until finally he reaches that place which you reach in all movies, where our hero gets to decide whether he’s gonna give up and go home, or carry on and kick some ass.

“The other main character in it is Darcy, an American in the French Foreign Legion, who has given up his life because his wife was killed, and is fearless basically because he doesn’t care if he lives or dies,” Henning continues. “So Houdin is in his fifties, and he’s got this beautiful French girlfriend, but all of a sudden there’s this strapping Mel Gibson-type [love rival] who is brave and silly. So when Houdin is finally faced with ‘shit or get off the pot’, the real reason he decides to shit is that Darcy’s going like, ‘Hey, you leave, I’m in bed with her five minutes later.’” After several drafts, Henning and Fain had a script which they felt was working. Commenting on the 116-page draft dated 30 April 1997, online script reviewer ‘Stax’ described the story as follows: “Houdin travels to Algeria (accompanied by Colette) for the purpose of demonstrating first-hand to the natives how Zoras’ sorcery is performed. Guiding and protecting Houdin and Colette on their dangerous journey is a detachment of French Foreign Legionnaires, led by the swashbuckling Captain Trey Darcy and his Spanish second-in-command, Corporal Augustino Bartolote.

“The group’s journey through Algeria is fraught with peril, as Zoras makes several sudden appearances (using actual magic?) to try and scare them off. During the course of this adventure, the one-handed Darcy (yes, that’s right, he fences with a wooden prosthetic!) and Colette discover a growing romantic attraction to

one another despite their respective obligations to Houdin. This rivalry for Colette’s affection, and his confrontations with Zoras, reinvigorates Houdin’s long-dormant vitality and his faith in himself and in the magic arts. Exposing Zoras’ trickery to his fellow tribesmen, Houdin succeeds in becoming a marked man. Houdin and the expedition must then flee the wrathful Zoras and his army of rebels. This draft culminates with an Alamo-like siege at a legendary desert fortress between Zoras’ forces and the cornered Legionnaires.”4 Overall, Stax saw Smoke & Mirrors (in Henning’s drafts, an ampersand replaced the ‘and’) as “a fact-based adventure chock full of romance, wizardry, David Lean-style vistas, and Golden Age of Hollywood production values.”

Despite the Batchlers’ assertion that Zoras’ men are Berbers, not Arabs, Stax had concerns about the fact that the heroes are essentially Colonialist occupiers, fighting Algerian natives — who, in reality, took 180 years to rid themselves of the oppressive French and win back their homeland. Henning’s answer to this moral quandary was to make Zoras so bloodthirsty and mad as to distance him from the other Arabic figures in the story, and ennoble the Colonial heroes. As a by-product of this, Stax observed, “Zoras is pretty one-note heavy in this story. He’s mainly a vessel for special effects, just as most of the other Arab characters are mere window dressing.” Stax felt that the romantic rivalry between Houdin, Colette and Darcy was handled well, however. “Darcy is a man of honour who finds himself drawn to the lover of the man he’s charged to protect, and who he finds lacking in how to treat a woman right. Darcy then becomes torn between his feelings and his obligation to duty. Subsequently, Houdin realizes what he stands to lose if Colette forsakes him for Darcy. This realisation helps Houdin snap out of being such a Grumpy Old Magician. (There are a few good jabs where people mistake Houdin for Colette’s father.) If Darcy is a man of action then Houdin is a man of thought who instead relies on his wits and experience. Both men turn out to be more alike than they figured, and they eventually form an alliance to battle Zoras.”

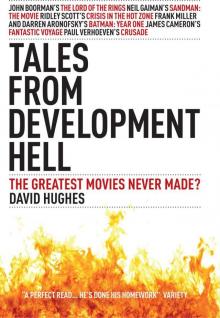

Tales From Development Hell

Tales From Development Hell